The first dandelion of the year showed up early.

This sign of spring appeared in the middle of February, in what has been a mild winter here in New Jersey—not the “wrathful nipping cold” of Shakespearean drama, but a temperate season that has reminded me about the possibilities of climate change and its challenges for farmers.

My little flower has benefitted from a few special factors. It has received a lot of sun from the south. It’s also rooted close to the house, which probably has reflected heat.

In this pleasant microclimate, it sprouted.

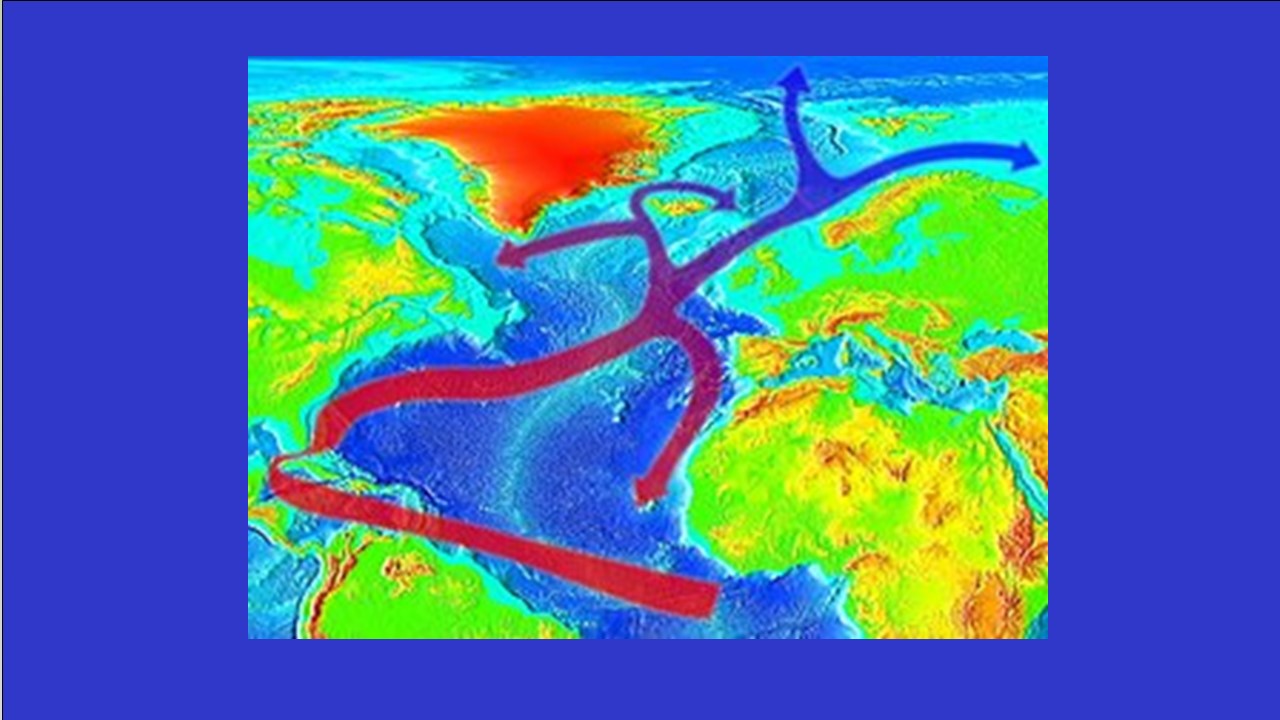

Around the time it appeared, I read an article about the Gulf Stream, the warm ocean current that starts in the Gulf of Mexico, runs north along the eastern seaboard of the United States, and shapes the weather in our region and beyond.

Apparently it’s slowing down.

A study released last fall claims that over the last four decades, the Gulf Stream has decelerated by 4 percent. The authors call it “the first conclusive, unambiguous observational evidence that this ocean current has undergone significant change in the recent past.”

What this means, assuming it’s true, is anyone’s guess, except to say that our world is dynamic and unpredictable.

A fading Gulf Stream also may affect the climate.

I believe climate change is real, but I’m no alarmist. The climate is always changing and we’re always adapting to that change and the weather it delivers. Every time you step out the front door, you make decisions and adjustments, choosing between coats and jackets, boots and shoes, and more.

Why should tomorrow be any different?

Farmers know all about climate and weather adaptation. Our economic lives depend on dealing with the problems of hot and cold as well as wet and dry. The prevalence of weeds, pests, and disease are also connected to the weather.

To farm is to adapt.

One possible result of a weaker Gulf Stream is harsher weather events. That means farmers in North America and Europe may find themselves selecting hardier crops that can thrive in shorter seasons and more extreme conditions.

Technology has supported the ability of farmers to adapt. The availability of GM technology over the last generation has allowed us to grow more and better food in a wider range of conditions. The newer innovation of gene editing, involving New Genomic Techniques (NGTs), also holds tremendous promise.

I’ve already made an adjustment on my farm: This year, I’m planting about 40 acres of sorghum.

The United States is the global leader in the production of this grain, which can be used for both human consumption and animal feed. It’s a tough crop that can grow in conditions that would wither or kill other plants. A single rain can carry it for a whole season.

I started growing sorghum years ago because I liked its hardiness. Yet sorghum has a challenge. It contains less protein than other staple crops. Pound for pound, it’s less valuable than corn.

The decisions about what to grow and in what quantities involve geography, soil quality, and crop rotation—and, of course, climate.

I stayed with sorghum when I discovered a niche market for it in bird seed. I’ve tended to think about agriculture in terms of food for people and livestock, so this was unexpected. It turns out that those sacks of “wild bird food” in garden centers and elsewhere are full of sorghum. Game birds such as quail and turkeys especially seem to like it.

Taking up sorghum was one of my adaptations as a farmer, based mostly on a demand for it but also with an eye toward climate conditions.

I have no idea how the climate will change in the decades ahead, what the farmers of the future will grow on the land that I’m working now, or whether the strength of the Gulf Stream will have anything to do with it. I assume my successors will make the best choices they can based on the information they have, the experience they’ve gained, and the information and technology available to them.

In other words, they’ll face surprises. They will assess, make decisions and will adapt, as farmers always have.

Looking out the window, I can see my next challenge: The lawn grass is starting to grow.